At any point before 2020, if you’d asked 100 people to explain who Sir Francis Drake was, how many do you expect would have led with ‘slave trader’? Even if you narrowed it down to 100 people who recognised his name, I doubt that more than one or two would do so.

But look how far we’ve come! A school in Lewisham recently announced, after a somewhat dubious survey of parents, teachers, local residents, and, er, 4-11 year olds, that it would rename itself from ‘Sir Francis Drake Primary School’ to ‘Twin Oaks’ over Drake’s involvement in the nascent transatlantic slave trade.

The school’s governing body had initiated this process because it said the old name was ‘at odds’ with the school’s ‘values’ - in essence, that Drake’s name is infamous. You might disagree, but the BBC did - at least initially - choose to describe Drake as a “16th century slave trader” in its article on the rebranding.

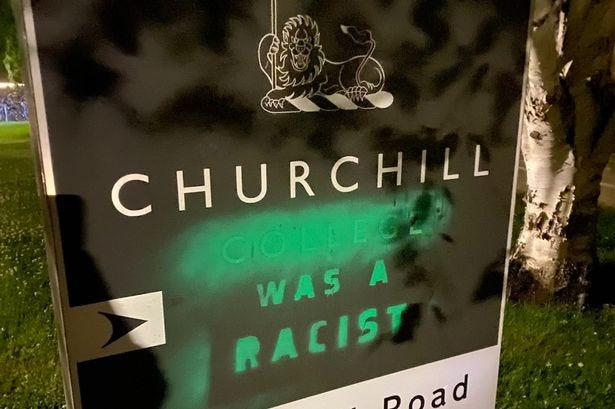

Once-respected figures from British history being ‘cancelled’ has been a trend at least since the rise of the ‘Rhodes Must Fall’ movement in Oxford around 2014, and it’s been turbocharged since summer 2020. Drake’s statue in Tavistock is now adorned with an ‘interpretation panel’ starting with a section about the slave trade. The local news article reporting on the panel’s erection repeatedly describes Drake as ‘controversial’.

Similar fates, from statues being toppled or ‘contextualised’, to establishments being renamed, have befallen a long and ever-growing list of historical figures. Multiple organisations, including the public and publicly-funded, have launched ‘audits’ aimed at identifying ‘links’ to the slave trade or the British Empire.

This is occasionally justified as simply an effort to ‘teach the whole story’ of these individuals, and of Britain itself, rather than what they call a ‘sanitised’ version. But this misses the point - we can’t teach the ‘whole story’ of anything, because, quite frankly, there’s too much to tell. Historical memory, in any context except the most rarefied heights of academia, necessarily involves a judgment about what we choose to talk about, and what we choose to bury.

Historians know far more detail about Drake than any reasonable person can be expected to absorb, so we prioritise what we think is important. For example, we’ve always tended to gloss over his tenure as Mayor of Plymouth, which gets one line in his Wikipedia page - apparently, he passed a law regulating the pilchard trade.

The last few years haven’t been about ‘teaching the whole story’, they’ve been about a conscious and dramatic shift in what parts of history we make a point of focussing on. The ‘slave trade’ section of Drake’s Wikipedia page, which didn’t even exist in its own right in May 2020, now amounts to 900 words, more than the same page manages about Drake’s role in defeating the Armada. The rest of Drake’s life is going the way of his laws regulating the pilchard trade, a footnote against the indelible stain of the words ‘slave trader’.

And so, the school governors decide Drake’s name is ‘at odds’ with the values of primary schools everywhere because of the slave trade. The BBC call him ‘slave trader’ before anything else. Clearly, a number of teachers, Lewisham residents, and schoolchildren are minded to agree.

Drake is a perfect example of how we’re living through a politicised effort to prioritise any ‘link’, however tenuous, to the slave trade or colonialism over anything else. There have been some valiant efforts to, er, contextualise Drake’s involvement in the slave trade in the 1560s, but honestly, what’s the point? It doesn’t matter to the people pushing this effort; and it shouldn’t matter to the rest of us. On no serious objective measure is Drake’s time on slave trading missions his most important contribution to British or world history - that would obviously be his defeat of the Armada.

A new and deeply unbalanced narrative of British history is being written before our eyes: one where our island story is little more than a succession of atrocities, most of them racist and the rest probably also bigoted in some way. Those whom we once recognised as heroes are now shamed as the perpetrators or accomplices of those atrocities.

This is what people mean when they accuse the ‘woke’ movement of ‘rewriting history’. In a purely semantic sense, history isn’t being ‘rewritten’ because no new information is coming to light - to my knowledge, literally everything we know about Drake today, we knew in 2020. But his Wikipedia page looks radically different, and that’s the point: the information that has the most weight, and gets included in the books and on the plaques, is changing.

It would be naive to assume this doesn’t have political consequences. After all, it’s no coincidence that this whole process got rocket boosters during the summer of BLM. Critical theorists believe that British history is a series of bigoted atrocities, and they believe that’s the origin story of the systemically oppressive hellscape they believe Britain to be today: a country whose entire culture, institutions, and even prosperity are built on the original sins of slavery, bigotry, and colonialism. You’re supposed to believe all of that too; and then you’re supposed to agree with their hard-left policy agenda. Other accounts of our history, of our current situation and how we got here, and of what we should do now all belong with the pilchard regulations.

If you do agree with this pretty bleak picture of Britain and its history, you’re likely to take a pretty dim view of Britain. You might be more likely to concur with Irish republicans who call our flag the ‘butcher’s apron’ than drape yourself in it. Why would you want to identify with the bad guys, especially if you can find some way of associating yourself with the good guys?

This is always going to weaken the foundations of British national identity. When the new narrative of our history inspires national shame, and our common (not ‘controversial’) inventory of national heroes and expressions of national pride is dwindling ever further, then ‘Britishness’ becomes less attractive and harder to pin down.

The latest British Social Attitudes survey made sober reading in this area. The last eight years have seen a precipitous decline in the proportion of Britons who believe this country is a better place than most others, and that the world would be a better place if people from other countries were more like us. The proportion who actively disagree with those concepts skyrocketed.

The only factor that a majority of Britons now believe is ‘very’ or ‘quite’ important for being truly British is ‘feeling British’, and 33% even think that doesn’t really matter. And among 18-34s, only 28% feel ‘very strongly British’, as opposed to 66% of over-65s.

There’s no absence of alternatives for people to transfer their identity to in place of Britishness (and, for that matter, Christianity). This includes alternative national identities - Scottish independence has over 60% support among 16-34 year olds, and Welsh independence is most popular with younger voters. The proliferation of EU flags since the Brexit referendum isn’t hard to notice either; and you can’t spend that long on Twitter before you encounter someone calling conservatives ‘flag shaggers’ while sporting about six or seven different flags in their handle or bio.

But increasingly, new sources of identity are also filling the vacuum left by traditional national and religious identities. As Lionel Shriver has noted, ‘identity’ is talked about more than ever, and invariably with reference to “the groups into which we were involuntarily born,” like race, ethnic ancestry, sexuality, and gender identity. The BBC has an ‘LGBT and Identity Correspondent’, and I think it’s fair to say that British national identity is unlikely to form a significant part of her remit.

What does this slow-motion shattering of identity, with different flags - national or otherwise - holding a greater place in more and more people’s hearts than the Union Flag, mean for Britain’s future. Like most nation-states, British identity is the glue holding the British state together, and the more it weakens, the more precarious the state becomes.

Scottish independence has hovered around 50% support for some time now. Welsh independence and Irish unification have significant minority support, especially among younger voters, and it’s not too difficult to imagine a ‘Yes’ vote in Scotland giving them a degree of momentum. And at that point, would you even bet against some of the wackier separatist campaigns that have developed online in recent years - Cornwall, London, ‘Northumbria’?

Yes. Yes, I would bet against them.

But that doesn’t mean England would emerge from a potential breakup of the Union as a happy or united place. English identity suffers from much the same demographic problem as British identity, if not more so. It’s likely that an English state would suffer from a weak sense of English national identity.

And suffer it would. Even if Britain survives its current identity crisis, it too is likely to suffer until the crisis is resolved. National identity, rooted in culture, language, and historical pride, is a powerful force for democracy and good governance. It’s open to newcomers, while still substantial enough to be meaningful; and it corresponds reasonably well to geography and existing borders.

When a national identity is weakened and gives way to other, more immutable identities that can’t be separated out easily by borders, then you end up with polities like Lebanon, or an early 1920s multiethnic American city, where social trust is low, and politics becomes less a matter of competence and ideology, and more a battleground of competing interests of the polity’s various identity groups.

Some British politicians have recognised that the decline in British identity is something to be slowed and reversed, but their response thus far has been relatively weak, focussing on a set of ‘values’ that nobody seriously thinks are specific to this country: the average Irish or Swedish or Japanese person would probably have no trouble subscribing to the full list of ‘British values’, but they’d be unlikely to agree that doing so makes them British.

The Government should consider taking a more forthright approach, stopping public support and funding for the new narrative of our history being pushed by critical theory advocates, empowering people to challenge that narrative when they encounter it, and reinforcing more tangible cultural aspects of our national identity.

Efforts to rename public or publicly-funded institutions, or remove or modify statues and memorials, could be subject to ample public consultation, ministerial approval, and a local referendum with a turnout requirement, for example. The Government could fund a fact-checking unit to challenge and correct defamatory misinformation about British history. We could have a national holiday - May 1st is the anniversary of the Union of 1707, and a day of traditional cultural festivities across the country.

Unlike many Western democracies, Britain has historically tended to shy away from ‘nation-building’ exercises like these. There are many reasons for that, but I suspect one of them is a complacency that’s becoming increasingly misplaced. If we like this country and want it to continue to exist - let alone be harmonious, prosperous, and well-run - then we should act now to rebuild our positive historical memory, and with that, the national pride that binds us together.